Repeat DUI Offenders: The Importance of Matching Services by Risk and Need

Change is hard, and the more it is required the harder it is to achieve. We have exhausted all of the simple-minded, one-size-fits-all policies derived from one-dimensional thinking. It is time to think in two dimensions, risk by need, and tailor our interventions accordingly.

Human beings rarely change on their own. Few of us have the requisite insight to see that change is needed, the judgment to know what steps to take, and the courage to move forward. The more we need to change, the less likely we are to do so. Some people are so lacking in insight, judgment, or courage that self-change is next to impossible. When their actions harm others, change must be leveraged by those affected, such as their parents, children, employers, or the criminal justice system.

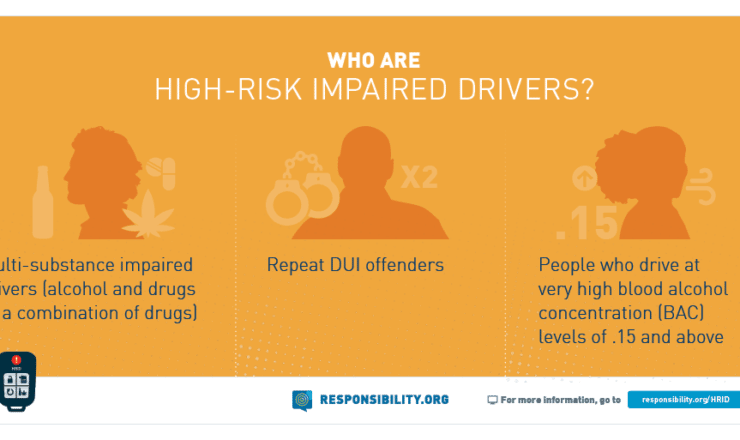

The justice system refers to such persons as high need and high risk. High need means that change is essential yet high risk means it is also unlikely. Healthcare providers use equivalent terminology: diagnosis and prognosis. A serious diagnosis means treatment is essential and a serious prognosis means the likelihood of recovery is questionable. Competent healthcare dictates that a clinician should provide more intensive treatment for a serious diagnosis or prognosis, and less intensive treatment otherwise. Too little treatment allows the disease process to progress, and too much treatment risks undue side-effects for minimal gain.

Unfortunately, the criminal justice system understands little about the two important dimensions of risk and need. Offenders typically receive services based on the nature of their crimes and the happenstance that appropriate services are available, their attorney or probation officer knows about those services, and the judge and prosecutor are supportive. Needed services are rarely received, the person’s condition typically worsens, and public health and public safety are threatened as a result.

Consider DUI offenders. One way to intervene with this population is to increase monetary fines, license suspensions, and/or jail sentences in response to successive offenses. The one question for lawmakers and politicians is how stiff to make the penalties. States with sparse populations, long and isolated highways, and libertarian attitudes may choose to increase penalties slowly. Those in dense environments with progressive views may impose penalties more steeply. This one-dimensional thinking fails because it neglects risk and need. We need to get two-dimensional.

Putting aside for the moment first-time DUI offenders, many of whom will not re-offend, no population suits the definition of high risk better than repeat DUI offenders. By definition, these individuals persist in a course of conduct offering few rewards and foreseeably disastrous consequences. Few populations are as deficient in introspection, blithe to consequences, and boundlessly impulsive. What value, alone, could increasing future and speculative penalties have for persons who think only about the present and are always certain they won’t get caught (this time)?

Some repeat DUI offenders are not only high risk but also high need. Not only has the threat of punishment failed miserably to make a dent in their behavior, but they may be addicted to drugs or alcohol and/or seriously mentally ill (frequently depressed and suicidal). No amount of wishful thinking will get them to desist from crime without treatment. No, this does not mean we should be lenient with them and divert them out of the justice system into treatment. High risk means they are unlikely to go to treatment, stay in treatment, or pay attention to treatment if left to their own devices. Without careful supervision and immediate consequences for noncompliance, no amount of treatment, no matter how well structured or intentioned, will have any effect. The only interventions proven to work for this population blend treatment with supervision in a closely-knit, multidisciplinary program. The best example is DUI Courts, which bring to bear the combined power and expertise of the courts, treatment, probation, and law enforcement, while ensuring that due process is protected under the watchful eye of defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges.

But not all DUI offenders are addicted or mentally ill. Many, perhaps most, are egocentric and restless but not discernably ill. Substance abuse and impaired driving are just two of many antisocial behaviors they engage in. Treatment for them is not the answer. Effective programs for this population de-emphasize treatment and focus, instead, on careful monitoring of substance abuse and other behaviors, coupled with immediate and certain consequences for infractions. Examples include the 24/7 Sobriety Project, originating in South Dakota, and Honest Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (H.O.P.E.), originating in Hawaii. Short-term sobriety is achieved readily by this approach, but long-term compliance also requires cognitive restructuring of participants’ dysfunctional criminal-thinking patterns. They must learn, among other things, to think before they act, anticipate the consequences of their actions, and consider alternative courses of action that are likely to be safe and productive. Interventions such as Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT), Thinking for a Change (T4C), and Reasoning and Rehabilitation (R&R) have proven effective in this regard. Without such interventions, relapse and recidivism are apt to be the rule rather than the exception once the authority of the criminal justice system is terminated.

And, finally, what about the low risk and low need individuals who pick up their first DUI charge and are unlikely to recidivate? For them, none of these programs is indicated. Too much treatment or too much supervision is likely to make them worse. Brief educational interventions, such as safe driving courses or victim testimonials—which have little utility for high risk and high need individuals—are usually sufficient to curtail future misconduct. At a minimum, one can be more confident that first-time offenders are, indeed, low risk and low need if they attend all of the required classes and complete post-tests correctly. Reliable class attendance and knowledge acquisition can be partially diagnostic of low risk and low need.

This blog is authored by Dr. Doug Marlowe, Chief of Science, Law, & Policy at the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). Prior to his current position, Dr. Marlowe was a senior scientist at the Treatment Research Institute and an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. A lawyer and clinical psychologist, Dr. Marlowe has studied coercion in substance abuse treatment, the effects of Drug Courts and other programs for substance abusers involved in the criminal justice system, and behavioral treatments for substance abusers and criminal offenders. He is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association (APA). Dr. Marlowe has published over 175 articles, books and book chapters on the topics of crime and substance abuse. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the Drug Court Review and is on the editorial board of Criminal Justice & Behavior.

*The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation for Advancing Alcohol Responsibility (Responsibility.org) or any Responsibility.org member.*