Phase 4: The Court Process

DUI cases are notoriously complex and challenging to adjudicate. Even seasoned prosecutors admit that seemingly straightforward impaired driving cases can be difficult to try in court. Each state is different in its court structure, but the process is similar across jurisdictions, progressing from pre-trial hearings to plea bargaining to trial (if necessary) and to sentencing.

To learn more about DUI adjudication, access a free, online course aimed at providing prosecutors with the knowledge needed to try these complex cases. Offered by Responsibility.org in partnership with the National Traffic Law Center, Prosecuting DUI Cases is a multi-module training course that provides knowledge of preliminary case review and evaluation, trial preparation, alcohol toxicology, and common defense and trial tactics. Attorneys who complete the course are eligible for continuing legal education (CLE) credits subject to state reporting requirements.

Key Players in the Court Process

Prosecution

Lawyers affiliated with a prosecutor’s office typically represent the charging entity (usually the state, but sometimes a municipality, district, or county) in DUI cases. In a small number of jurisdictions, police officers may prosecute their own cases. Prosecutors’ titles vary, although they are commonly referred to as state attorneys, district attorneys, county attorneys, or city attorneys.

Prosecutors typically dismiss charges if they have a reasonable doubt about the defendant’s guilt. Charges can be refiled, though, if new evidence is discovered and the prosecutor believes the case is provable.

Throughout the adjudication process, prosecutors have significant discretion. They can negotiate pleas with defendants to avoid lengthy trials and eliminate uncertainty. When plea deals are arranged, defendants typically agree to plead guilty in exchange for more lenient sanctions. It is common for limits to be placed on plea bargaining in DUI cases to ensure that these serious criminal offenses are not pled down to reckless driving or comparable charges that lack an alcohol or drug component.

If a case is not resolved by a plea, prosecutors are responsible for preparing the case for trial. They must develop a case strategy, prepare witnesses, and create lines of questioning. During trial, prosecutors must deliver impactful opening and closing statements and be prepared to combat common defense strategies. It is the job of the prosecution to present the strongest case possible to the judge or jury. When convictions are secured, prosecutors make recommendations for the judge to consider at sentencing.

Judge

In criminal cases, judges always determine the law. In bench trials, they also decide whether the prosecution proved their case beyond a reasonable doubt and issue judgments. Throughout the criminal justice process, judges have multiple responsibilities:

- Making decisions about pre-trial release or detention.

- Ensuring the judicial process remains fair and orderly.

- Interpreting relevant case law and making rulings on motions.

- Accepting pleas (and ensuring that defendants enter these pleas voluntarily) if both sides arrive at an agreement.

- Determining what evidence can be entered into the record and/or admitted at trial.

- Making rulings on objections throughout the trial process.

- Providing instructions to the jury if one is seated.

- Assessing evidence presented at trial and if it is a bench trial, arriving at a judgment.

- Making sentencing decisions.

While judges often have a great deal of discretion, they may also be constrained by sentencing statutes. Many states have passed mandatory minimum sentences and other sentencing requirements based on prior impaired driving convictions. Judges are required to follow these guidelines although they may apply more punitive sanctions if they determine that the facts of individual cases warrant a harsher sentence. In addition to mandatory minimums, judges may also be constrained by the lookback period, which determines how far back the court can look when considering prior offenses for sentencing purposes. Most states have a lookback period of 10 years. (To determine a state’s lookback period, refer to the Responsibility.org State Map.)

Defense counsel

The primary function of defense counsel is to serve as a zealous advocate for their clients. They are responsible for ensuring that clients receives a fair and adequate defense to charges and should seek the best possible result. Throughout the criminal justice process, defense counsel advises their client about the options that are available, which can change over time as a result of plea bargaining with prosecutors.

Defense counsel is responsible for challenging the state’s case and for developing a strategy and tactics to sow reasonable doubt in the mind of the judge or jurors. If the client is convicted, defense counsel will put forth sentencing recommendations that aim for the most lenient sentence or conditions possible. The defense may also appeal the conviction and sentence if there is cause to do so.

DUI is a unique area of law because there is a highly specialized defense bar that only handles these types of cases. These attorneys are often extremely effective because of their experience and depth of knowledge on all DUI issues, legal precedents, and proven tactics. DUI defense attorneys also share information with one another, which makes them formidable opposition, particularly when the prosecutor is inexperienced in DUI cases. As a result, defense counsel often welcomes the prospect of a trial. High-priced attorneys also rely on expert witnesses to poke holes in the state’s case, and they often have access to individuals who are classified as “professional witnesses” and are exceptionally convincing in front of a jury and skilled at avoiding prosecutor questions.

For DUI defendants who do not have funds available to hire a lawyer, the court appoints a public defender to represent them and oversee their case. These individuals are classified as indigent and

under the Sixth Amendment, the government is required to provide them with free legal counsel to ensure that they have fair representation during criminal proceedings.

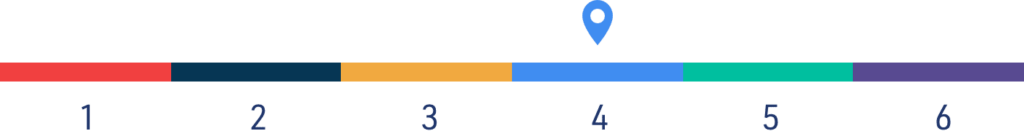

Key Steps in the Court Process

Cases have the potential to be resolved at numerous points in the court process. Not every impaired driving case makes it to the trial phase, and both the prosecution and defense work to resolve cases in a manner that attempts to satisfy all parties.

Initial Appearance and Bail/Bond Decisions

An initial appearance before a judge typically occurs within 24 to 48 hours of the arrest and detention of a suspect. This may also be referred to as a bail/bond hearing or preliminary hearing. The judge will determine whether the criminal complaint has merit and the defendant understands the process and is fit to proceed. Some jurisdictions have separate preliminary hearings where the state is required to show that there is sufficient evidence to establish probable cause that a crime was committed and that the defendant is the individual who committed the crime. This is similar to a grand jury in that the prosecution bears the burden of presenting enough evidence to establish probable cause and the defense is not required to submit evidence of its own.

The judge rules whether the state has established probable cause. If this burden has not been met, the defendant is released. If there is probable cause to support the charge(s), the judge then considers if the defendant should remain in custody pending trial. As part of this decision-making process, the judge considers recommendations from both the prosecution and defense counsel. In misdemeanor cases, the defendant may be offered a chance to enter a plea. A felony case is always set for arraignment.

For more on the pre-trial process, see “Phase 2: Awaiting and Preparing for Trial.”

Arraignment

The main purpose of an arraignment in a DUI case is for the defendant to enter a formal plea in court. In some instances, particularly misdemeanor cases where the defendant has been released from detention, the arraignment will be the first formal step in the criminal process. It may not occur for weeks or even months following the initial arrest.

During the arraignment process, the defendant is advised of his or her constitutional rights. If the defendant does not have legal representation, the judge will inquire whether a continuance is necessary to afford the individual time to obtain counsel or qualify for a public defender. There are four plea options available to a defendant:

- Guilty plea

- No contest (nolo contendere)

- Not guilty plea

- Request for deferred judgment or diversion

If a defendant pleads guilty, sentencing may occur the same day. But it is more common for that individual to be referred to probation to begin the process of compiling a pre-sentence report. A formal sentencing hearing will be scheduled for a future date.

A plea of nolo contendere or no contest is essentially a guilty plea. The legal implications are the same with the exception that the plea cannot be used against the defendant in civil proceedings. In the context of impaired driving cases, if a crash victim sues an impaired driver for damages, the no contest plea cannot be used as evidence in the civil trial.

A not guilty plea triggers the next phase in the process, which could mean setting the case for trial as well as scheduling a pre-trial conference or preliminary hearing. The pre-trial conference allows both sides the opportunity to negotiate a plea agreement. As the case progresses toward trial, the prosecution is required to begin turning over evidence to defense counsel, and the latter will review the evidence to determine the strength of the state’s case. Defense counsel will continue to advise their client of the various options that are available to resolve the case.

Lastly, a request for deferred judgment or diversion can be made when a defendant meets eligibility criteria for participation in certain programs. If the prosecutor agrees to allow the defendant to participate in the program, that individual must abide by all conditions and complete all requirements to have charges dismissed. Failure to complete the program results in traditional prosecution.

If a defendant fails to appear for arraignment and does not have an attorney appear on his or her behalf, that individual violates a court order and a bench warrant will likely be issued. The defendant is then subject to arrest and detention pending a hearing to address the new charge resulting from the failure to appear.

Pre-Trial Conferences and Hearings

The pre-trial conference process consists of a single hearing or several hearings scheduled between the defendant’s arraignment and trial date. These hearings are scheduled to ensure that the case is progressing and that both the prosecution and defense will be ready to present their respective cases.

During pre-trial hearings, evidentiary matters and motions are typically addressed. The prosecutor attempts to have all evidence that points to the defendant’s guilt admitted at trial. The defense seeks to damage the state’s case and fights to have unfavorable evidence excluded. In cases where the defense intends to introduce evidence, the prosecution may file motions to exclude it.

During these hearings, a judge will frequently rule on motions that seek to limit the scope of evidence and arguments that can be made during trial. Common motions in impaired driving cases include:

- Motion in limine (motion to suppress evidence): In DUI cases, the defense frequently files these motions for one of a few reasons: evidence was obtained due to an illegal stop or search; a confession was obtained without proper Mirandizing of the suspect; standardized field sobriety tests (SFSTs) or other protocols were improperly administered; breath test results are flawed due to issues with the testing procedure or equipment; there are chain of custody issues related to evidence such as blood draws.

- Motion to exclude testimony: Another form of a motion in limine is a Daubert motion, which seeks to exclude the testimony of an expert witness by proving through a preponderance of evidence that the purported expert does not possess requisite expertise or that a specific scientific technique that they will testify to does not meet the standard for admission of scientific evidence.

- Motion for discovery: Either the prosecution or defense may claim that the opposing party has failed to turn over all evidence in the case. If a violation has occurred, the court may order compliance and/or impose sanctions, including, in appropriate situations, exclusion.

- Motion to obtain preserved blood: The defense may request that the preserved sample be turned over so it can be subject to testing at an independent laboratory.

Plea Agreements

Plea bargaining is a negotiation between the prosecution and defense. Most criminal cases, not just DUIs, end in a plea agreement rather than proceeding to trial. Due to backlog, scheduling conflicts, and limited resources, it is not possible for every criminal case to advance to the trial stage. Plea bargaining affords each side the opportunity to reach a positive outcome. This also removes the uncertainty that surrounds a trial as a plea guarantees a specific resolution.

A common compromise reached in DUI cases is a guilty or no contest plea on the part of the defendant in exchange for a more lenient sentence. While conducting plea negotiations, the prosecutor must take into consideration the opinions of the victim or the victim’s friends and family. If a plea agreement is perceived as “too lenient” or merely a “slap on the wrist” by victims, they are likely to question whether justice was done and may lose faith in the criminal justice system. Prosecutors should keep victims apprised of any plea negotiations and discuss potential agreements before moving forward.

Plea bargaining in DUI cases is controversial, and in some jurisdictions state law limits the ability of prosecutors to accept guilty pleas to lesser charges in impaired driving cases.

It was once common practice to plead impaired driving charges down to reckless driving or a comparable traffic offense. The removal of the alcohol component in these plea deals created significant issues when offenders came back into the system as a result of a subsequent DUI. Due to previous plea bargains, second offenses were treated as first offenses, and the offenders were not subject to the enhanced penalties that they should have faced as repeat offenders. While it is necessary for prosecutors to resolve DUI cases in a timely and effective manner, it is also important that defendants who fail to change their behavior and commit additional impaired driving offenses be subject to sanctions and treatment requirements that reflect their repeat offender status. For this reason, many prosecuting attorney’s offices do not permit DUI defendants to plead to lesser charges. The same rationale should also apply to defendants who successfully complete diversion programs. If they are arrested for a future DUI offense, the first conviction that was removed from their record should be reinstated.

Once the prosecutor and defense agree to a plea bargain, it is presented to the judge in court. In most cases, a judge may accept or reject a plea deal. The judge must assess whether the punishment that the prosecution and defense have negotiated is appropriate given the charges as well as the defendant’s criminal history, risk level, and other facts of the case. If the judge determines that the agreed upon sentence is too lenient or that it is not in the interests of the victim(s) or general public, then he or she may reject the plea deal and articulate the rationale for doing so. In some jurisdictions, the judge may have the discretion to accept the plea agreement on specific terms but reject the sentence or defer his or her decision until a pre-sentence report is complete. Similarly, a defendant may have the ability to withdraw a plea if the judge rejects the sentence. Should the negotiated agreement fall apart in court, both parties have to agree to new terms or proceed to trial.

If the judge accepts the plea agreement, the defendant pleads guilty and is subject to the terms of the sentence outlined in the agreement.

Trials: Bench and Jury

When the prosecution and defense cannot negotiate a plea, the case proceeds to trial. In criminal cases, a defendant has the right to choose whether to be tried by a jury of his or her peers or by a judge. This decision may be made for the defendant if their case is being adjudicated in a low-level court that does not empanel juries, but typically, defense counsel will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Bench trial

In a bench trial, the judge is the trier of fact. Bench trials tend to be less time-consuming as there is no jury selection process and the judge is not required to give jury instructions. Bench trials may also be less formal than jury trials and less complex. This tends to be the preferred format when the major issues at trial surround technical legal arguments as opposed to facts entered into evidence. Another potential benefit of a bench trial is that the trier of fact is educated about the law and is required to be impartial as a function of their role and therefore, is less likely than a jury to be swayed by emotion. If a defendant elects to have a bench trial, the judge determines guilt or innocence and, should the defendant be convicted, that same judge hands down the sentence.

Jury trial

In a jury trial, the triers of fact are individuals selected from the community where the trial occurs. The jury is supposed to be composed of a group of the defendant’s peers. Once empaneled, the jury applies the law according to the judge’s instructions and determines whether the prosecution has met the burden of proof. Trials that involve juries tend to take longer due to the additional steps required:

- Jury pool: Members of a jury are selected from a pool of community members who report to court after answering a jury summons. In most states, eligible jurors are selected from a list of licensed drivers or registered voters.

- Voir dire: Not every person who responds to a jury summons is selected to sit on a jury. Prospective jurors are questioned under oath during the voir dire, or preliminary examination, process. Both the prosecution and defense attempt to seat a jury that is likely to view the case that they present favorably.

- Juror challenges: Cases can be won or lost based on jury selection; therefore, both sides attempt to seat the strongest jury possible. Throughout the voir dire process, both the prosecution and defense challenge jurors who they believe are incapable of remaining impartial or have an identifiable bias that makes it unlikely they can fairly decide the case. This is considered a challenge for cause, and in these instances, the judge will determine whether the juror should be dismissed. In addition to cause challenges, each side also has a limited number of peremptory challenges that can be exercised to dismiss any juror within their discretion, so long as they do not do so based on improper factors like race, religion, or ethnicity.

- Juror selection: The number of jurors required to serve on a jury in a DUI case varies by state. Once there are no more challenges available or if both sides are satisfied with the prospective jurors who are seated, the jury is officially empaneled. In high-profile or serious cases, alternate jurors may also be selected. Immediately after the jury is selected, the judge provides the group with specific instructions and rules that they must follow. Jurors who violate instructions risk being dismissed.

Jury trials tend to be a preferred option when the defense plans to dispute the facts of the DUI case. Juries are comprised of lay individuals who do not have an in-depth understanding of the law and, as such, it is often easier to sway their opinion. Both sides attempt to cultivate the jury’s sympathy. Prosecutors highlight the harm or potential harm caused by the defendant, whereas defense counsel is likely to minimize the seriousness of their client’s behavior. Another bias that defense counsel may seize upon is distrust of law enforcement. If the bulk of the case hinges on officer credibility, it is in the defense’s best interests to seat a jury that is likely to question the actions of law enforcement. A final advantage of jury trials is that there may be opportunities to appeal a verdict if the judge’s jury instructions can be called into question.

Trial Process

Once a DUI trial commences, it follows a predetermined format:

- Opening statements

- Presentation of the state’s case and examination of state witnesses

- Presentation of the defense’s case and examination of defense witnesses

- Closing arguments

- Instruction to the jury and deliberation (if applicable)

- Verdict/judgment

Opening statements

The prosecutor and defense counsel each have an opportunity to make an opening statement to the judge or jury. An effective opening statement from the prosecutor should communicate the nature and extent of the defendant’s impairment, focusing on the big picture, but highlighting the most important evidence (BAC level and incriminating statements, fox example). Good trial lawyers are storytellers, and prosecutors should endeavor to make their opening statement compelling and offer a theory of the case that explains why the DUI occurred. A strong opening statement concludes in a powerful manner and tells the judge or jury what can be expected at the conclusion of the case.

Prosecution’s case

The prosecution presents its case first and introduces physical and scientific evidence and witness testimony. The defense has the opportunity to challenge the admission of evidence on various grounds and also cross-examine any witness. If a prosecution witness’s credibility is damaged under cross, the prosecutor can attempt to rebuild their standing through another round of questioning called re-direct.

In advance of trial, the prosecutor should begin preparing witnesses which involves meeting with them, learning about their personal history, reviewing all written statements or prior testimony to refresh their recollection, anticipating and prepping witnesses for possible defense questions and challenges. When dealing with individuals who have never testified, the prosecutor should give those witnesses a tour of the courtroom and walk them through the process of testifying.

In DUI cases, it is common to introduce expert testimony. States have different standards for determining who qualifies as an expert witness but generally, a witness is qualified as an expert by demonstrated knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education. Common expert witnesses in impaired driving cases include law enforcement officers, Drug Recognition Experts, breath test technicians, forensic toxicologists and crash reconstructionists. Collaboration with law enforcement is particularly important in DUI cases as officers can help identify potential problem areas in the case that can be mitigated during the prosecutor’s presentation of the facts.

Once the prosecution presents all of the state’s evidence and witness testimony, the state rests.

Defense case

The strategy of defense counsel is largely influenced by the strength of the case that the prosecution was able to build. The burden of proof is on the prosecutor, and if the defense is able to call into question the evidence or testimony, then they may be able to “rest” without introducing any additional testimony.

An experienced attorney is likely to have several defense strategies ready to be deployed and if the client has sufficient resources, the defense may secure the testimony of its own expert witnesses. Defense counsel look to suppress state evidence and undercut and refute testimony. The defense frequently attacks several aspects of the impaired driving investigation including observations of the vehicle in motion, observations during the officer’s initial contact with the defendant, administration of field sobriety tests, use of breath test instruments and their results, and officers’ findings of impairment. Every prosecutor should anticipate several common arguments:

- The stop was invalid because the officer lacked reasonable suspicion.

- The arrest was invalid because the officer lacked probable cause.

- Tests and protocols for detecting impairment were performed incorrectly or lack validation.

- Evidence collected from the investigation should be suppressed because the defendant was not properly Mirandized.

- Breath test results should be suppressed because the breathalyzer was not functioning or calibrated properly.

- Blood test results should be suppressed because a warrant was not obtained, or the blood draw was not performed according to procedure, or the chain of custody was violated.

If the defense calls any witnesses, the prosecution has the opportunity to subject those individuals to cross-examination and question their credibility. The defendant is not required to testify in his or her own trial, and attorneys often advises against taking the stand as it opens their client up to questioning. Once defense counsel is satisfied that reasonable doubt is established, they rest their case.

Closing arguments

Closing statements are the final opportunity for the prosecution and defense to present their interpretation of the facts. The prosecutor should clearly outline all of the evidence presented and explain the applicable DUI law. It may be necessary to respond to key arguments that arose during the trial and offer explanations for any defense arguments. Inconsistencies in the case should be contrasted with the strength and totality of the evidence.

Jury instruction

When a DUI case is tried before a jury, the judge must provide instructions before the jurors begin deliberations. Instructions are often dictated by state law. In some instances, the judge may provide instructions that inform the jury that if the prosecution was able to establish certain facts beyond a reasonable doubt then they must find the defendant guilty. In other situations, a judge might read the jury a formula instruction that includes the relevant law and outlines all of the conditions that must be proven in order to convict. The judge may also define certain terms like “impaired,” “intoxicated,” or “under the influence.” Defense counsel might also propose specific jury instructions that could favor their client.

Verdict or judgment

In a jury trial, a verdict is delivered and in a bench trial the judge enters a judgment in the case. After the judge provides the jury with their instructions, they deliberate and review the evidence presented at trial. If jurors are uncertain about testimony or discrepancies exist between various jurors’ recollections, a request can be made to have transcripts read out or for specific pieces of evidence to be reviewed. There is no required format for how deliberations occur. To arrive at a verdict,

the jury must be unanimous in its finding. If the jury remains undecided after a period of lengthy deliberation, the judge will be notified that the jury is hung. At this point, a mistrial is declared, and the prosecution can elect to re-try the case.

If the jury is able to reach a unanimous decision, the judge is informed, and the parties reconvene. The verdict is read in open court and the defendant is found “guilty” or “not guilty” of the charges. A finding of not guilty indicates that the jury determined that the state did not meet its burden of proof. If the defendant is found not guilty, he or she is free to go and cannot be re-tried.

In a bench trial, the judge schedules a hearing when he or she arrives at a decision. Instead of a verdict, the judge enters a written judgment into the record that outlines the rationale behind the decision based on the preponderance of evidence and interpretation of relevant law. In most impaired driving cases (except for serious felonies), the defendant is free on bail at the time of trial and, if found guilty, will remain under community supervision until a sentencing hearing is scheduled. In the interim, the judge may order a pre-sentence investigation to collect relevant information about the newly convicted DUI offender to inform the sentence.

Pre-Sentence Investigation and Report

Pre-sentence investigations are common in criminal cases and are often mandatory for felonies. Throughout the course of a pre-sentence investigation, probation officers collect information the offender’s criminal record, findings from screening and assessments conducted as a result of the current offense, interviews with family members and other associates, interviews with probation officers or treatment professionals, and home visits. A thorough PSR should contain the following:

- Summary of the offense

- Criminal history

- Driving record

- Record of compliance while under community supervision

- Medical history

- Mental health history

- Alcohol and drug use

- Screening and assessment outcomes

- Treatment history/prior admissions

- Personal and family history

- Education

- Employment history and current employment status

- Financial/socio-economic status

If a screening and assessment was not conducted at any point during the pre-trial phase, it should be done as part of the pre-sentence investigation. To obtain an accurate offender risk level and identify criminogenic and treatment needs, the instruments selected should be validated specifically for the impaired driver population. (Learn more about screening and assessment and recommended instruments here.).

A list of program options and treatment interventions that are well-suited to the DUI offender’s risk and needs should be compiled and provided to the judge along with the PSR. If victim restitution is likely to be part of the sentence, the PSR might also contain a proposed payment schedule and list other fines and fees that the offender is required to pay. It may be necessary to gather a realistic assessment of the individual’s financial situation and ability to pay restitution as well as other fees. In the case of an indigent offender, the court may need to identify possible funding streams to ensure that inability to pay is not a barrier to compliance with court-ordered supervision conditions.

While the pre-sentence investigation takes place, the convicted DUI offender typically remains under supervision within the community. Depending on the jurisdiction, responsibility for supervision may shift from pre-trial services to probation. A judge may impose additional conditions during this time if deemed necessary.

Sentencing

The final step in the court process is the sentencing hearing. In addition to the findings in the PSR, the judge must also consider relevant statute and any mandatory sentencing guidelines when imposing sanctions.

The sentencing hearing provides both the state and defense counsel the opportunity to make their own recommendations to the judge. Each side presents evidence and testimony to the court to support their respective positions. The prosecutor stresses the level of harm that the offender has inflicted. When formulating sentencing recommendations, the prosecutor should research what intervention options are available in the community that are appropriate for the impaired driver population and present these options to the judge. The prosecutor should not assume that the judge is familiar with effective DUI countermeasures.

The defense attempts to paint the defendant in the best light possible and provide reasons why he or she should serve the sentence in the community with the least restrictive conditions possible.

The sentencing is one of the few opportunities for victims to play an active role. Through victim impact statements, which are often read in court by the victim or a representative of the victim, the innocent parties affected by the offender’s actions can articulate how they have been impacted by the criminal behavior as well as the judicial process. Victim impact statements remind the court of the damage that impaired driving inflicts upon society and how this entirely preventable crime can have lifelong implications for innocent people. Victims are encouraged by both prosecutors and victim advocates to take advantage of the opportunity to address the court as it gives them agency and a voice. No one can articulate the pain and suffering caused by impaired driving better than an innocent individual who has had his or her life irrevocably altered by this crime. The statement should conclude with specific requests for sanctions.

After the prosecution makes recommendations and the court has heard from the victim, the defense typically attempts to garner the judge’s sympathy in a plea for mercy. It is common for family members, friends, and other acquaintances to offer testimony or submit letters of support that attest to the character and societal contributions of the offender. The defense may be able to receive leniency by demonstrating that the void left in the lives of others or the community would be detrimental and significant if overly punitive sanctions, such as lengthy periods of incarceration, were imposed.

Mandatory minimum sentences and other sentencing requirements may apply. These requirements tend to be more common in felony cases, which means that repeat impaired drivers are more likely to be subject to mandatory minimum sentences. Overall, each judge should seek to balance public safety with the rehabilitation of the offender.

Several important principles can guide judicial decision-making in DUI cases:

- Swift, certain, and meaningful sanctions should be applied in every impaired driving case.

- Impaired drivers have a multitude of issues, and the court misses an opportunity to intervene in a meaningful way if the focus is solely on identifying and treating alcohol dependence. Many DUI offenders are polysubstance offenders and may have co-occurring mental health disorders.

- Cookie-cutter sentences are not appropriate for the high-risk impaired driver population. The judge should focus on individualizing justice as each DUI offender has specific risk factors, criminogenic needs, and issues that may require treatment interventions. Assessments must drive decision-making. Treatment interventions should be tailored to the individual, and the judge should endeavor to maximize responsivity by making referrals to programs that address the person’s specific needs.

- Accountability is key and if an offender is not adequately supervised, behavior change is unlikely.

- Technology, while extremely useful, is not a replacement for supervision. Monitoring is needed to ensure that the offender is compliant.

Types of Sentencing in DUI Cases

A variety of sentencing options are available to judges in DUI cases, and the judge frequently orders a combination of the following sanctions:

- Incarceration: The length of the jail/prison sentence is dependent largely on the severity of the impaired driving offense.

- Community supervision: Most impaired drivers, including those who are sentenced to a period of incarceration, are also required to serve part of their sentence in the community under supervision by probation officers.

- House arrest: This is a more stringent form of community supervision as it is essentially a period of incarceration served at the individual’s residence. When a term of house arrest is ordered, the individual is often subject to GPS monitoring and is only permitted to leave the residence for court-approved reasons.

- License suspension/revocation and other driving restrictions: The court has the authority to suspend or revoke an individual’s driver’s license as a way to protect public safety. The court may also restrict driving privileges and only permit an individual to operate a vehicle for specified/limited purposes.

- Ignition interlocks: In states that have either judicial-based or hybrid ignition interlock programs, it may be the judge’s responsibility to mandate that an offender install an ignition interlock as a condition of their sentence. In these instances, the court must communicate with the licensing authority (the DMV or its equivalent) and provide the agency with the sentencing information. Some states impose these measures administratively.

- Vehicle sanctions: In addition to licensing sanctions, the court may also impose vehicle sanctions such as impoundment or immobilization. These tend to be more extreme options that are not frequently used.

- Fines: The application of fines is a common sanction in DUI cases, and the amount is often set by statute. In addition to fines, the offender may also be required to pay certain fees to cover administrative costs associated with the judicial process.

- Community service: The nature and extent of community service in DUI cases varies considerably. If community service is ordered, the offender must spend a certain number of hours volunteering with a non-profit or public works agency within the community. One popular option is requiring the offender to volunteer with victims’ rights or advocacy groups and speak to audiences about the consequences of driving impaired.

- Screening and assessment: If screening and assessment for both alcohol and drug use disorders has not been performed at the time of sentencing, the judge should order the completion of this process immediately and schedule a follow-up hearing to make a determination about the need for treatment. In addition to assessing substance use, the judge may also consider ordering screening and assessment to determine if the DUI offender has co-occurring mental health disorders or trauma that needs to be addressed. If this comprehensive screening and assessment is not completed, the court misses an opportunity to intervene and address all underlying factors associated with the individual’s behavior.

- Treatment: The rehabilitation of an offender who has substance use or mental health issues must be considered at the time of sentencing. If a judge has reason to believe that the offender has substance use issues or continued use places the individual or the public at risk, then it is imperative that participation in and successful completion of treatment be part of the sentence.

- Alcohol and/or drug testing: In cases where significant concerns exist about an offender’s substance use, testing requirements are often imposed as a condition of the sentence. In some instances, the judge may prohibit an offender from consuming alcohol or using drugs and use various testing methodologies to enforce the condition.

- Victim impact panel attendance: Another common sentencing option in DUI cases is mandatory attendance of a victim impact panel. These panels are comprised of victims and DUI offenders who share their stories and detail the affect that impaired driving has had on their lives. The goal of these panels is to provide victims with an outlet to share their experiences and to help impaired drivers to understand the consequences of their actions and deter them from driving under the influence again.

Once the judge enters the sentence into the record, the offender is required to abide by the conditions of probation. Jurisdiction or authority over the offender shifts from the court to the appropriate monitoring agency—the Department of Corrections or another body that oversees incarceration and community supervision. If an offender is non-compliant with the sentencing conditions or commits another offense, he or she may be returned to the court for a violation hearing or to answer to the new charges. The judge has the ability to revoke probation or impose additional sanctions. In rare instances, defense counsel can appeal a sentence if they can show that the sentence is illegal, unconstitutional, or excessive.

Administrative sanctions

In addition to judicial sanctions, DUI offenders are simultaneously subject to administrative penalties imposed by the state licensing authority (the DMV or its equivalent). As a condition of re-licensing in the majority of states, DUI offenders are required to serve a period of administrative license suspension/revocation, pay various fees, install an ignition interlock and comply with all interlock program requirements, and complete remedial programming in the form of alcohol education or treatment.

Resources

Responsibility.org’s Screening and Assessment Position Paper for Legislators (Responsibility.org, 2025)

A Guide to Pre-Trial Services (Responsibility.org, 2020)

Law Enforcement DUI Testimony, Silver Tips Checklist (Responsibility.org, 2020)

International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP)

Cannabis Impairment Detection Workshop Handbook (Responsibility.org, 2020)

National Law Enforcement Liaison Program (NLELP)

National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA)